- Home

- Johanna Skibsrud

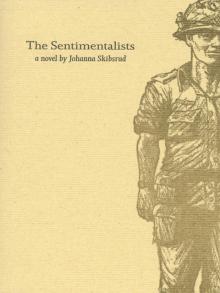

The Sentimentalists

The Sentimentalists Read online

THE SENTIMENTALISTS

The Sentimentalists

a novel by Johanna Skibsrud

GASPEREAU PRESS LIMITED

PRINTERS & PUBLISHERS

2009

Text copyright © Johanna Skibsrud, 2009

Illustration copyright © Wesley Bates, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the prior written consent of the publisher. Any requests for the photocopying of any part of this book should be directed in writing to the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency. Gaspereau Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Nova Scotia Department of Tourism, Culture & Heritage.

Although some passages may be based on real people, places and events, this is a work of fiction and not a literal depiction.

Typeset in Joanna by Andrew Steeves and printed and bound under the direction of Gary Dunfield at Gaspereau Press.

7 6 5 4 3 2

LIBRARY & ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Skibsrud, Johanna Shively, 1980–

The sentimentalists / Johanna Skibsrud.

ISBN 978-1-55447-078-5

I. Title.

PS8587.K46S45 2009 C813’.54 C2009-901899-3

GASPEREAU PRESS LIMITED · GARY DUNFIELD

& ANDREW STEEVES · PRINTERS & PUBLISHERS

47 CHURCH AVENUE, KENTVILLE, NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA B4N 2M7

For my mother

i sing of Olaf glad and big

whose warmest heart recoiled at war

E.E. CUMMINGS

Contents

Fargo

1

2

3

4

5

Casablanca

1

2

3

4

Casablanca 1959

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Vietnam 1967

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Epilogue

Fargo

1

The house my father left behind in Fargo, North Dakota, was never really a house at all. Always, instead, it was an idea of itself. A carpenter’s house. A work in progress. So that even after we moved him north to Casablanca, and his Fargo home was dragged away – the lot sold to a family from Billings, Montana – my father was always saddened and surprised if the place was remembered irreverently, as if it had been a separate and incidental thing; distinct from the rest of our lives. In this way, he remained, until the end, a house carpenter. If only in the way that he looked at things. As if all objects existed in blueprint; in different stages of design or repair.

The Fargo place had been acquired by my father in the first year of his sobriety, and by that time it had already been pieced together from two and a half aluminum trailers and deposited in a lot – No. 16 – at the edge of a West Fargo mobile-home park. To him, and therefore to us, it was always his “palace” nevertheless, and he looked on the additions and renovations that he made to the place over the years of his residency there with particular pride.

The park itself was crowned by a large blue and white water tower and the surrounding landscape of West Fargo was so flat that my father could follow the tower, from the other side of town, all the way home. He could drive straight across the city on the carefully sectioned right angles of highway, and it looked, as he approached the park, as if the neat rows of long, low houses were, for the tower, a structural necessity. It also appeared that the park was in the tower’s full shade. But, as he approached – as he passed the last four-way intersection and his own house came into view – the tower diminished, the houses lengthened, small front gardens appeared, and there was suddenly space for two or three cars in every drive. By the time he pulled into his own driveway, the water tower, although still large, was a peripheral structure six or seven blocks away.

The additions to the house had been made awkwardly before my father arrived, so that, from the side, the building appeared to be attached by several loose joints. Inside, the linked sections were marked by a step, and because the corridor was so narrow and long those steps were as much of a surprise to come across as a curve would be on a prairie-town street.

At the end of the corridor was the room my father referred to as the “second library” – the “first” having reached its limit years before. My father was a great reader and a great rememberer of things, though he never remembered anything in the right order, or entirely, and always had just little bits of all the books and poems he’d ever read floating around in his mind. The second library was the most lived-in room of the house and stored (besides the shelves of books that gave to it its name) the computer, the TV, the exercise bike, and the photographs, in piles.

The photographs had been mostly those sent, over the years, by my mother and grandmother, and I knew them all well because they were the same ones kept in albums at my mother’s house. They were of my sister Helen and me: posed for yearly school portraits, or else with our feet up on soccer balls.

Our early years were documented well in my father’s house. There were shots of backyard camping, of our first dog (a golden lab named Roger), as well as stacks and stacks of Christmas concert photos, in which it is nearly impossible to identify a single subject.

A gap of four years in the progression of the photographs left most of our adolescence unaccounted for, so that, in going through the piles on my first visit to my father’s house, at the age of twenty-two, I was surprised to find us – toward the end of the collection – suddenly grown. The documentation resumed itself only in sheets of uncut wallet-sized graduation photographs, and then in the newer, less dusty images of my niece, Sophia, which Helen had sent from Tennessee.

The second library was the designated smoking room when I visited. My father retired there after meals, and at half-hour intervals throughout the day. I avoided the room and tried to keep the rest of the house aired out as best I could. Sometimes, though, I would get it into my head that, like my father, I couldn’t breathe – and then I would run back and forth along the corridor and swing the front and back doors quickly in and out.

In my father’s last winter in Fargo, too out of breath to continue repairs on the palace, he became interested in the stock market. He upgraded his computer and after that spent nearly all of his time in the second library, rarely venturing into the long corridor that led to the rest of the many-roomed house.

He had set up the computer on a low desk next to the television, so that it was possible for him to watch them both at once, and he kept up on the progress of his few shares throughout the day, even watching them while he logged his obligatory mile on the exercise bike, which he had moved in front of the screen. When the markets closed in the evenings and on holidays he missed them and paced the room, he said, “like a bear.”

The computer was part of a package deal that he paid for so slowly that the interest soon turned out to be double the cost. “I’m even getting a burner thrown in,” my father told me over the phone in January, “and a fax machine.”

“Doesn’t all this depress you a little?” my sister Helen said a month later when my father’s operations were in full swing.

“Dad,” I said, “what in the hell are you going to fax?”

He didn’t hear.

“I might as well,” he told me. “At this price I can’t afford not to.”

By the third week of my father’s career he had lost a total of $150 which he pointed out to us was pretty decent for a newbie.<

br />

“This is much safer than blackjack,” he told me when he tallied the results and let me know.

“This might be the wrong economic moment, Dad,” I said, “to get into this sort of thing.”

“You may be right,” my father admitted, “you may be right.”

But my next communication from him was an e-mail he sent to both Helen and me, and it looked as though he had no intention of pulling out. It read, “Keep your fingers crossed and we’ll be retiring to the original Me-hee-ko in very short order.” Another message followed this one closely. “I’ve given up on the miners, but – doing a little research, and, third time being the charm, our next venture’s going to put us in the running, my sweethearts. Hope you’re feeling as lucky as I am.”

Helen wasn’t feeling lucky at all. “We’ve got to get him out of there,” she said. “Henry will never put up with this shit.”

Henry’s place, tucked into the tiny town of Casablanca, Ontario – just twenty miles from the border of New York – was the site of all our childhood summers, and what all of us, including my father, secretly thought of as home. Still, when Helen first suggested that my father move there permanently to be looked after by Susan, Henry’s part-time nurse for as long as we had known him, my father clung resolutely to the independent refuge of his palace, which he returned to every year, like a bird. But that next spring, after the stock-market winter, we moved my father, despite his protests, permanently to Casablanca. The palace was sold, according to Helen’s direction, shortly before his departure, and it was arranged that my father’s files be transferred to the North Country Veterans Clinic in Massena, New York, from where Susan – now fully employed – could drive his medication across the border, without delay.

It’s a tall, upright building, Henry’s house. Constructed on government money to replace his old family home which was one of twelve original houses lost when the dam came through in 1959. Even now, Casablanca is a small town, but before the dam it was not even, properly, a town at all. It was only referred to by its intersecting county roads, and because of this was never officially recorded as being “lost.” It wasn’t until the dam came through that people started calling the place Casablanca. Because of the way that, like in the Bogart film, they had begun to “wait for their release” from a town that – never having fully existed – had already begun to disappear. But then, even after the relocation was complete, the name stuck, and came to refer to the new community of government-built houses that got strung along the lake road.

Although many of the original homes were, like Henry’s, buried, or otherwise burned to the ground, some had been simply lifted from their foundations and carried the short distance into town. Even the year before, with the construction of the St. Lawrence seaway, it had been anticipated that even the older houses could be so cleanly removed that residents were encouraged to leave everything in place inside them. For the most part, this advice went unheeded. People packed their belongings into boxes anyway, placing them in relative safety, in the corners of the rooms. But there were those who, curious to test the claim, left candlesticks on narrow ledges in the halls, books balanced upright on countertops, and chipped teacups on high kitchen shelves.

One resident who left two mayonnaise jars balanced one on top of the other in the middle of her living-room floor had found them – upon re-entering her house fifty-two hours later and at a distance of several miles – upright still, as though they themselves were the axis upon which everything else had turned, seemingly less bewildered by their journey than she herself had been.

Henry’s old place still lies buried some miles from his front door at the end of the disappearing road, which begins on one side of a small island and empties out into the water again on the other.

The dock at the end of the government house drive still points like a long finger in the same direction, and at the end of the dock, Henry’s old boat is tied.

The remains of the rest of the original town (if that is what it can be properly called) can sometimes still be seen below the lake road, which runs from the town limit to an archipelago of islands in the middle of the large created lake: sections of fence posts, a crumbled church steeple, and pieces of the old foundations, which are marked at the water’s extremity by long poles that stick out at odd angles around the edge of the lake – a warning for the boats that go racing by sometimes with their motors down, too fast.

2

My parents hadn’t split yet when we first drove north to Casablanca to visit Henry, and we all lived together in the house that my father had built. It was a tiny place, tucked into the back of the woodlot we owned, just outside the paper-mill town of Mexico. That house had also been a work in progress; a three-room cabin, clad in tar paper. Its inner workings – a network of exposed water pipes and electric wires – were always bare on the inside walls. Its front steps were missing, too; we’d always just gone in around the back.

The progress of the house was stopped entirely in the spring before I was born, when my father began work on The Petrel, a wooden boat built for my mother. It was a project that marked for him a spring of such passionate and uninterrupted enthusiasm, that, by the time I was born, he was hardly coming home at all. He slept, more often, curled up next to the boat in Roddy Stewart’s old shed in town, and it was because of this that on the afternoon of my birth my mother drove herself to the hospital, my sister Helen in tow.

If, in the summer that followed, my mother complained – that she had been abandoned by my father, left all alone in the world, with two small children and a half-finished house – my father would reply with a wink and a wave, and in one small gesture describe to her perfectly the curve of the bow, or the slant of an imaginary sail.

If, when my father spent what my mother later claimed was their literal last-dime, in order for the actual sails to be sent (they were shipped, in mid-December of 1981, all the way from Delaware), my mother complained that they had eaten nothing but celery for a week, my father would remind her once again of the contoured coasts of Maine and Nova Scotia. From Booth Bay Harbour to St. John’s.

The plans for my father’s boat had also been sent away for, and I remember that – years later, in a renaissance evening – the blueprints would be spread around our kitchen as my father consulted them, promising once again that we’d be sailing by spring. But as I hovered to watch, and my father made fantastic, undecipherable scratchings with his carpenter’s pencil on the page, I began to believe that the blueprints of my father’s Petrel (where the constellations of lines and images had been drawn in the finest of ink, and on the thinnest of paper, which I thought hardly intended for human hands) depicted vast and astonishing kingdoms that were voyageable to him alone.

My father himself was not a water man – so when, in the summer of her abandonment, he was able to comfort my mother with the articulate gesture of an imaginary sail, it was because it was my mother and not my father who loved the sea. If it had been up to her, we would not have settled inland, but on the great and open Maine coast instead, the waters of which she had known as a child, having spent her vacations there, and which – even in my own earliest memories of it – remained still largely untouched and wild. It had become fixed in her mind. A blueprint for all of her future happinesses, which she could still, on those occasions, name.

It had been, after all, within those brief sea holidays that her own father had woken from his year-long nap to become, again, a human being – orchestrating great sea hunts in which the entire family scoured the tidal pools for clams. In which they speared fish, and tied white chickens onto lines in order to catch the blue crabs, which flocked like flies to the bait. And so it was the ocean that, for my mother, became the great elemental figure that was either missing, or to some degree at hand, when she searched in later years to solve the problem of her own and my father’s lives, and I think now of what a shame it was that the joy that we, her own children, later found at the lake with Henry and my father was somet

hing that excluded her. And that she passed on her own love of the water only through the stories that she would sometimes tell. Stories that made her seem, instead of closer, only further away – as though she surrendered herself, in the telling of them, to her own, separate, antediluvian underworld, which was what (influenced, I suppose, by the buried town of Henry’s backyard) we imagined all stories to be.

In the loneliness of the summer of my birth, in which my father slept in town, my mother experienced on occasion pangs of such sudden and unexplainable grief, that, so sure was she that it had become a physical affliction – that it had begun directly attacking her heart – she would often drive, with us in the backseat, all the way into town to Roddy Stewart’s old shed to tell my father, in a resigned undertone, so as not to upset us, that she was dying.

This was another complaint that my father could always allay. He would smooth out her hair over her temple and forehead, and kiss her in the particular place that he had designated, behind her ear, for the specific communication of his love – which he sometimes found hard to say out loud – and tell her in no uncertain terms that very soon they would sail together in The Petrel of the white sails, paid for by a month of celery. My mother would apologize, her heart appeased. She would run her hand over her face and, with a little laugh (which served to establish the event in the already distant past), say, “I hardly know what came over me.” By this route she returned to her more usual self, and she would pile us back into the car and drive home. Of the event she would make only a small note in the journal she kept in which to record our lives: another episode today, she would write. Followed by a record, as near as she could render, of the last thing that she had thought of or seen before the exquisite pain had begun. Tomato plant. Obscure memory of Aunt Rose.

In this way my mother attempted to uncover a pattern or a system to her grief, but there never did appear to be one, and the pain continued to erupt equally from the sight of an old photograph as from an untwinned sock. But after each entry my mother would go on to conclude: it should not happen again. And this conviction – that unhappiness, in herself and later in her children, should be staved off, then eliminated entirely – originated from that same source within her that assured her that the progress that my father was making on his boat, and that my mother was making on my father, and that my father’s words were making on her heart, would be measurable and lasting things, upon which each of us could build.

Island

Island Tiger, Tiger

Tiger, Tiger Quartet for the End of Time

Quartet for the End of Time This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories The Sentimentalists

The Sentimentalists