- Home

- Johanna Skibsrud

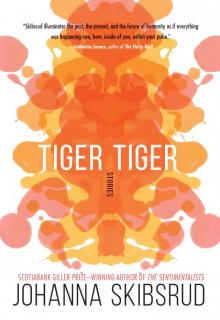

Tiger, Tiger Page 2

Tiger, Tiger Read online

Page 2

Needless to say, it was during this brief period that I had the fortune (or the misfortune, depending on how you looked at it) of publishing my single article. Had it not been for the dodo craze, my small, rather zany paper would probably never have made it past a peer review. In any case, it put a feather in my cap to have my name in print so young, and the piece no doubt contributed to my subsequent hire. But then, of course, shortly after I joined the department—and though the dodo population continued to thrive—interest in their existence fell off dramatically. Almost overnight, I became a dusty academic, the equivalent of a stuffy professor of Latin who continues to insist, despite all evidence to the contrary, on the sustained value and influence of dead languages.

It was for this reason that I now seemed doomed to share an office, in perpetuity, with Dr. Wolff, whose own research was also impossibly out of date. (I had often acerbically suspected that the respect Dr. Wolff still commanded was based on nothing more than his tenacity, the fact that he had now been around “longer than anyone could remember.”)

* * *

—

It was really no wonder, when you thought about it, that the dodo had gone so quickly out of fashion. That squat, definition-less body, that dull, nearly expressionless gaze…It was impossible not to be consistently reminded of their origin: of the fact that they, more rather than less literally, were a species of the walking dead.

A tiger, on the other hand! There was a figure to capture—and sustain—the imagination. Long enough, at any rate, to publish another article. Perhaps, I considered, I could even manage a whole book before enthusiasm for the idea completely ran its course!

I indulged myself for a moment or two in imagining how I might introduce the topic to future readers: by describing how the idea had first come to me, in the dusty confines of the office “I still shared, at the time,” with Dr. Wolff. I would mention the jars: those hundreds of unseeing eyes stacked on the upper and lower shelves—witnesses, all, to the idea as it took shape, and a new life (at once human and more than human) began to stalk its way through the undergrowth of my mind…

* * *

—

By the time I got word that the department had approved my application for funding, I had already run the whole project—from its inception to its glorious completion—several times through my mind. Still, it was a surprise to learn that the application had been accepted—and still more of a surprise when, only a week later, I received word from the institute in Moscow that the genetic material of the last Siberian tiger was mine.

I remember I was still in a state of near shock the evening after receiving the news. Franziska had just returned from a conference in Dubai, and when I arrived home from the office she was busy emptying her suitcase, sorting its contents on the bed and folding everything into neat little piles.

I made her sit down. I took her wrists in my hands and sat her down on the bed, disrupting the piles. My heart was beating in my chest like a wild thing that had found itself unexpectedly enclosed.

“What is it?” she asked.

I did not immediately reply. I couldn’t. I pressed her wrists toward my chest. I felt a steady pulse beneath my thumb and was unsure if it was hers or mine.

“Come on,” she said. Her voice was irritated, or alarmed.

She gave her wrists a shake. I released them.

“The tiger,” I said. “The tiger…It’s mine.”

And then, of course, I had to tell her everything from the beginning, starting with Dr. Wolff, because I had not yet breathed a word of it to her, or to anyone—save to the departmental review board and, of course, to Dr. Singh.

For some time, it had actually been quite difficult for me—even under more ordinary circumstances—to speak with Franziska about my career. We had married during the dodo craze; Franziska was still in graduate school then. There had been no reason to suspect that my career would not continue as promisingly as it had begun.

It wasn’t long, however, before I was more than eclipsed. Franziska was now one of the top researchers in the life-extension sciences, and I had yet to publish a single book.

She could hardly have chosen a more fashionable field. While I was staring at the preserved remains of human and animal specimens, and perfecting the art of just-barely-not-listening to Dr. Wolff, Franziska was being courted by just about every major university, science journal, and television network. Her opinion on everything—from the most innovative research being conducted, to the sort of breakfast cereal a person should buy—was sought out and incorporated into advertisement copy and household conversation. Almost every week she had some new engagement: a radio or television interview, a corporate consulting project, an award ceremony, a commencement address.

More often than not she travelled alone, mostly because of the restrictions of my own schedule. This was fine by me. I hated tagging along with her, and she knew it. I couldn’t help but withdraw—to feel that whenever I stood at her elbow and someone asked me, “And what do you do?” that it was a form of direct attack. Even, or especially, if they happened to express interest: “Oh, how absolutely fascinating, I never would have thought,” or “And how did you choose that particular field?” My skin would prickle and my throat would dry out, so that I would have to reply in short gasps, quickly shutting down the possibility of further communication.

The antagonism I sensed was (as Franziska insisted to me the one time I mentioned it) “all in my head.” (Note: I had not intended to mention it at all; it was Franziska who brought it up, chastising me after some function or other for having a “defensive, even combative reaction” to the subject of my work.) “By lashing out,” she said, “you create the problem you later identify as your reaction’s cause, when in fact, you see, it is only an effect.”

Perhaps she was right, but that did nothing to change how much I dreaded being caught in a room with her and a throng of other life-extensionists. I could practically hear them wondering to themselves why someone like Franziska had chosen to spend the rest of what would, no doubt, be a very long life with someone like me.

But that was one of Franziska’s many charms: her own seeming imperviousness to what other people thought. She had a “fresh outlook,” according to the press, a “unique voice”—was even something of a “visionary.” In a world devoid of Romance after the devastations of the Last War, she was a romantic. With nothing to return to, she continued to long desperately for a more “natural” course of things.

It was her job not to subvert or alter this course, she maintained, but to attain it more fully—to move closer to, rather than further from, the “essence” of the natural world. It was not all hot air: her more recent scientific studies all convincingly demonstrated that this was indeed possible. That a natural “essence” could in fact be distilled—could be isolated and removed from such chance outcomes as disease and old age.

Her announcement (casually, last spring, in the course of a television interview) that she was considering naturally conceiving, and bearing, a child, should not have come as a shock to anyone who had been closely following the trends in Franziska’s career. It was in line with both her romantic impulses and her predilection for all things “organic”—yet she surprised everyone. No one, perhaps, more than me.

In recent years, the life-extension sciences had made childbearing virtually obsolete. If—as it now appeared, thanks to Franziska’s own dedicated research on the subject—human beings had the capacity to live as good as forever, we quite simply didn’t have the resources to support any future generations. Not, at any rate, until the food science and space travel industries had been given the opportunity to catch up.

According to the press, Franziska’s desire to have a child was something she “felt deeply”—something she really “couldn’t explain”—but the first time I’d heard anything about it was by watching the six o’clock news. Because of this, I couldn’t help but suspect, in less generous moods, that Franziska had first take

n an interest in the idea more or less as a publicity stunt.

Perhaps she had been inspired by the genetics professor we had shared in our university days (it was in his class that Franziska and I had, in fact, first met), who had augmented his reputation in the field with the idiosyncratic detail, known to everyone, that he was the adoptive father of twelve. How could a life-extensionist like Dr. Franziska Scheller (everyone, as she well knew, was bound to wonder) bat away the threat of extreme overpopulation her chosen field of science had virtually invented, with the mention only of a “deep desire” she couldn’t otherwise explain?

I should have guessed, of course. Long before Franziska’s announcement on the six o’clock news. Franziska later said so herself—as if the misunderstanding between us had somehow been my fault. If I had been “paying attention,” she said…

And it was true. I might certainly have noticed that for nearly a year, no matter where she was in the world, Franziska had flown back each month for at least a twenty-four-hour period—during which time I was placed under the most direct of pressures to perform the necessary function of my sex.

After long absences, these pressures were—at first, at least—most welcome. But after Franziska made her announcement, her urgency to conceive a child increased dramatically. So abrupt and so direct was the pressure I was now under that I often found myself quite unable to perform.

This drove Franziska nearly mad with distraction. What was I was afraid of? she asked. Did I not truly love her? Want her to bear my child? Did I think it was wrong? Was my reaction (or rather, my lack of any reaction at all) a judgment, in whole or in part, on her and her desires?

Again and again, I promised her, on all counts yes, when it was appropriate to do so, and on all counts no, when that was instead the answer required. And indeed, though my initial reaction to Franziska’s announcement had been one of skepticism and surprise, it was not long before I, too, began to feel something I “couldn’t explain”: a feeling that, once detected, I realized must always have existed—but so “deeply” within me, I had never suspected it was there. And so, on most occasions it was not on account of either fear or reluctance (as Franziska suspected) but on account of my own almost unbearable desire that I—quite literally—shrank from my task.

You can only imagine Franziska’s disappointment, after having taken a red-eye flight from Auckland or New York or Shanghai. And though, in the end, we always somehow managed, they were nights I would rather forget.

And still—after months, now, of the most concentrated efforts on both our parts, we were no closer to achieving our goal. This placed our personal relationship under considerable strain. Rather than resulting in any direct conflict between us, however, it diluted something. We became abstract; each to the other only half the idea we were attempting to express.

But what was that idea? It was a question that, though it remained unspoken, charged every thought or remark that passed between us. Even the most ordinary statements seemed to end on an elevated note.

It was becoming evident that, contrary to what we had always thought, there was, between us, nothing “essential”—that our relationship was the result of nothing more than dumb chance.

There was a time when we would have exalted in this. In the pure “luck” (we had called it then) of our having met one another at all. In the inessential details of behaviour and form that had—by first capturing our attentions—led us near blindly into love. I had been struck, for example (almost literally; I remember the sensation, like being pulled under by a sudden wave), with the way that Franziska adjusted her eyeglasses when momentarily disconcerted or confused, by the small dimple that appeared in the high upper left corner of her cheek when she smiled. It was impossible to guess what litany of gratuitous details had first inspired Franziska to notice me, but they had existed. Despite her personal and professional proclivity for the “essential” and the “absolute,” there is no doubt that, at the beginning, she had as little a grasp of my “essence” as I had of hers.

What was now becoming clear was that, even after the many years we had spent with one another, we had moved no closer toward an understanding.

Testament to this was Franziska’s reaction when I mentioned the tiger.

* * *

—

“But have you considered the thing fully?” She had risen from the bed and had turned her attention back to her disrupted piles.

My hands, which had been raised, dropped to my knees.

Considered the thing fully…I ran the words a second time through my mind. Did she realize how preposterous they sounded? How absolutely counter to science? How on earth, I wondered—exasperated—could one fully consider what did not yet exist? What was only an idea, a matrix of possible circumstances, arisen from a previous matrix of possible circumstances?

And how could Franziska, who knew this (and who knew, too, that this was the first genuine opportunity I had so far been granted in my entire career), respond in this way? What was required was not consideration, I reflected anxiously, but a simple decision: was one, or was one not, willing or able to take what, even in the most scientific terms, could be called nothing other than “a leap of faith”?

Yes! I was willing! Of course I was! I could feel it—my own willingness—trembling inside me, like a plucked wire.

But instead of explaining this to Franziska, I said only: “Of course I have!”

My voice was harder than I had expected it to be.

“Excuse me,” Franziska said, and tugged at the sleeve of a button-down shirt, which I had pinned beneath my knee.

I got up quickly and the shirt flew toward her, unfolding itself and waving like a flag at the end of her hand.

“I mean,” I implored her—the sudden panic in my voice accelerating rather than softening my tone—“what is there to consider? We are faced with…a prospect, a genuine opportunity. I should instead be asking you, have you considered the matter? I mean, truly. Have you tried, even for a moment, to grasp what this means? What it could begin to mean…for me personally, yes, but also for the future of science? Of history? Of the world—not as we know it, but as we might one day begin to imagine it to be?”

Franziska was silent. Carefully, painstakingly, she folded the shirt and placed it on the bed.

“And what about for him—or her,” she said, very quietly. “For the tiger. Have you considered it from her perspective? You’ve told me yourself,” she continued, carefully, “how unique the tiger is among mammals, how curiously human their emotional responses have been observed to be. That they can feel genuine rage, sorrow. Have, if threatened, been known to take elaborate, performative, revenge. Have you considered how this emotional capacity might develop, or express itself, in a specimen like the one you describe—one that’s been cut off from even the possibility of contact and communication with its own species, from the very idea of history, and, therefore, from any sense of what it even means to be a tiger? It strikes me,” she concluded, “not so much as a question for science but as a moral dilemma!”

Now I was genuinely annoyed. “Oh, morality!” I said. “Nice of you to mention it. Need I remind you that I’ve been turning this question over for my entire career? That the moral dilemma to which you refer is the very basis of any study of the deep past, and of the possible future—the two regions to which my field of research is particularly and devotedly bound? While you”—I took a deep breath—“you and your esteemed colleagues have been busy extending our lives beyond all reasonable limits at the expense of countless future generations whom you have barely paused to consider, I,” I said, “have been moving at a snail’s pace, floundering in semi-darkness, searching for any possible foothold…Do you remember my dissertation?” I asked. “The complex argument I developed, the questions I broached—specifically against the advice of my advisory committee, who warned me not to get ‘in too deep’? Do you remember ‘Die zweite Auferstehung’ in Progressiv Biologie Heute?” I took another deep b

reath. “Do you remember the dodos?”

Franziska stared at me, her face blank. She appeared suddenly tired and—the thought surprised me, but once it had been thought I could not un-think it—old. Not in any physical sense, of course. Not to be vigilant about something like that would not be “eccentric” in Franziska’s line of work; it would be career suicide. There were no lines or wrinkles around her eyes, and her body was as slim and lithe as it had always been; her hair was as sleek, her skin as fresh and as smooth as on the first day we met. But there was something new…something…Then it hit me. I had perceived—distinctly, and in that exact moment—a genuine change. In Franziska, or in my relationship toward her. A change that, though it had no doubt taken place slowly, over time—though it had in this sense always been occurring—had also occurred in precisely that moment. And I had witnessed it.

But that I had witnessed it…did this not suggest that a change had occurred in me as well? That I, too, had—over the time Franziska and I had known one another—grown old?

The idea did not frighten me. Instead, I felt a sudden, distinct pleasure at the thought. Even—yes, arousal. Something stirred in me. I approached Franziska. I extended my hand toward her and touched her cheek—the exact place where, if she smiled, a dimple would suddenly appear.

She was not smiling now. Nonetheless I knew exactly where the dimple would be, and touched it.

Did she soften—even slightly—at my touch?

I let my hand fall gently, so that my palm cupped her cheek. At first she did not respond at all, but then, slowly, very slowly, she relaxed the muscles of her neck and allowed me to support the weight of her head and neck in my hand.

Then, very suddenly, she drew back. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m—very tired.” She returned to her task.

Perhaps I should not have reacted so fiercely. The “moral” question had become particularly charged between us of late, and I knew very well she was still feeling sensitive. It had come up when, only a few weeks before, we read together the findings of a new study conducted by a team of geneticists (one of them none other than our own former professor) about the discovery of a “moral code” within the basic structure of human DNA. The research team concluded that one was either born with the “moral gene” or one was not. An argument had almost immediately erupted between Franziska and me, which, rather than being resolved, had merely petered out into a short exchange of such statements as “Well that’s your opinion then,” and “I suppose I’m not going to change your mind.”

Island

Island Tiger, Tiger

Tiger, Tiger Quartet for the End of Time

Quartet for the End of Time This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories The Sentimentalists

The Sentimentalists