- Home

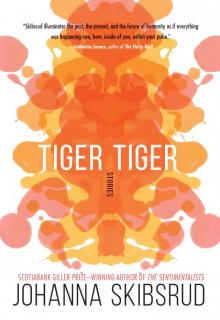

- Johanna Skibsrud

Tiger, Tiger Page 4

Tiger, Tiger Read online

Page 4

They had reached the metal doors that led to the building’s central auditorium. At other times, card games were held here, the occasional movie was shown. Gina pulled one of the doors open partway so that Hero could peer inside. The tables had been pushed against the walls and plastic chairs were set up in rows. About twenty or twenty-five resident “guests” were seated, mostly in groups of twos or threes. They filled roughly half of the available chairs. At the front of the room was a low stage, where—behind a pressboard table evidently serving as an altar—the celebrant rocked patiently from heel to toe, in a slow, rhythmic motion. He was wearing a bright red button-down shirt, tinted prescription glasses, and orthopaedic sneakers.

The groom stood to his immediate left, arms dangling awkwardly. He was twenty-five roughly, of medium height and weight, and vaguely familiar to Hero, though she couldn’t say why. His suit didn’t fit properly; the shoulders of the jacket were too broad and the pants were too long, slouching over a pair of scuffed-up black trainers.

“Pomp and Circumstance” was being piped in through the small speakers at the back of the room. There were white streamers and a few vases of plastic flowers at the head of the stage.

Hero checked her watch: 1:43. And the ceremony hadn’t even started yet. Usually she stayed only about half an hour. Sometimes less—twenty minutes or so. Hero would ask Kitty how she was feeling and then sit there nodding—periodically contributing a small, sympathetic exhale—while Kitty rattled off a list of her latest complaints.

Even before her memory had begun to go, it was rare that Kitty asked a single question.

Then the two of them would watch Zoe on TV together and about midway through Hero would announce that she regretted she couldn’t stay longer. She’d give Kitty’s hand a squeeze, a quick peck on the cheek, then leave her to watch the next six broadcasts of the six o’clock news. All the rooms at Paradise Valley were hooked up to cable, and Kitty could have watched Zoe on Channel 10 any day of the week at the regular time, but, of course, she always forgot. Last Christmas, Hero had bought her a slow-mo subscription, and they now recorded all of Zoe’s broadcasts. When she came on Tuesday afternoons, Hero queued the system so that after watching the previous Tuesday’s broadcast together, Kitty could watch the rest of the week’s broadcasts in a single go. And she did watch—positively rapt. Exclaiming all the while in delight over Zoe’s hair and makeup. Even when she momentarily forgot who Zoe was, it didn’t seem to matter. Hero had wryly reported as much to Zoe on more than one occasion. “Space and time simply melt away,” she had said. “You transcend.”

The few times that Hero had stayed with Kitty long enough to watch more than one broadcast, she had found it unsettling. The democratic sincerity of Zoe’s voice so significantly undercut the distance between reported events that, before too long, Hero found she could no longer distinguish between them. A story about a woman driving off a bridge into the San Luis Rey River, for example, and a story about early voter registration struck her as disconcertingly parallel.

Adding to the confusion was Kitty. She would beam at the television from across the room, periodically exclaiming, “What a pretty girl! What a very pretty girl!”

* * *

—

“Go on,” Gina said. She indicated Kitty, who was seated alone, about midway down a central aisle. She was wearing a turquoise pantsuit with a tricoloured pastel scarf, her signature bouffant dyed an iridescent blue. Hero made her way down Kitty’s mostly empty row. She hunched her shoulders a little, apologetically, as if that might make her appear smaller. At the front of the room, the celebrant was still shifting patiently from foot to foot and the groom—whom she now recognized as one of the attendants—stood by as if awaiting final judgment.

Yes, of course—that was it, Hero thought. She had often seen him pushing the residents to and from the cafeteria, his face set in exactly the same mixture of resignation and dismay.

Hero touched Kitty’s shoulder and Kitty turned, beamed. “Sweetheart!” She took up Hero’s hand and gave it a firm squeeze. “You made it!” she said. “I’m so glad.”

Long before her memory went, it had been one of Kitty’s strategies to be extravagant and impartial with affection. On the one hand, it guaranteed that she didn’t offend anyone who presumed themselves of some importance, and on the other, it flattered those who didn’t.

Hero sat down, feeling irritated. Again, she looked at her watch: 1:46. Okay, she told herself. I’ll give it till two. She was usually out the door by two anyway. Or shortly after. She looked toward the double doors at the back of the auditorium, where presumably the bride would shortly be arriving. Then back toward the front.

Really, she should just slip out now. Leave a note on the whiteboard: “Nice to see you, Grandma!”

What more, on any other occasion, did her visits amount to?

It was, for some reason, the doily covering the pressboard altar toward which she now found her attention drawn. What a truly preposterous object, she thought. And yet, she could clearly recognize within it (perhaps, indeed, it was the very origin of) her own “aesthetic and creative development.”

She remembered how, on the few occasions she’d visited Kitty in Hancock Park as a child, she’d followed her grandmother about—lingering over the polished china figurines on the mantelpiece, which, once or twice, she’d even been permitted to lift, briefly, in her hands. She remembered how absolutely transported she had been by their shimmering forms. Life was not a series of objects, they seemed to suggest, but of possibilities, of angle and light!

Yes, it was from Kitty—with her spoon collection, her doilies, her candelabras and porcelain figurines—that Hero had first learned about beauty. Her mother had always emphatically avoided the word, but Kitty used it all the time. A painting or a flower was beautiful—but so was a sweater, or a chicken sandwich.

Hero, too, had been beautiful. She remembered the distinct pleasure she used to feel when Kitty drawled out a compliment to Hero’s long legs or fine hair. It was a vexed pleasure, because of the way that her mother always stiffened in reaction to the word, but it was a pleasure nonetheless.

In their own household—the drab log home her father had built for them outside Spokane, with its serviceable little kitchen garden—the word “beauty” referred only to museum art, symphonic music, or things that happened to people in books. In her grandmother’s house, beauty was a thing you could touch. It was crocheted doilies and glass lamps. It was long hair, lean calves, air conditioning, and the scent of Nuits de Paris.

The door at the back of the room screeched open, and two overweight girls in peach-coloured dresses came marching slowly down the aisle. Nurses, or nurse’s aides, Hero thought. But she didn’t recognize them.

Kitty patted Hero’s hand as they passed, then turned, craning her neck to watch the door.

* * *

—

At LACMA right now, there was this James Turrell retrospective going on.

Hero had gone last week with her friend Anjali. “It used to be like this,” Hero had said, gazing at a projection of a fluorescent square on the wall. “Art was everywhere, wasn’t it? It used to be enough to say—look.”

Anjali had twisted her mouth into a knot and nodded. The two of them sat down on a bench opposite the projected square.

It was difficult to know when to stop looking.

It used to be, Hero considered, as she followed Anjali into the next room, that a limit was a suggestion, an invitation. Nowadays, it was just a limit. It was a raised eyebrow, a shrug. Quotation marks hovering like a set of claws around any idea made vulnerable by hesitating too long in the air.

In the hologram room, she passed her hand through each of the images.

It is not an illusion, she thought. She could see it quite clearly: the way her hands actually disrupted something.

By the time she looked up, Anjali had moved on, and that was why, several minutes later, she ended up wandering alone into “Key Lime, 199

4.”

* * *

—

The room was so dark that upon first entering, Hero had to walk with her hands stretched straight out in front of her so she wouldn’t bump into anything. She could make out a dozen or so shadows—people moving through a green light at the centre of the room. Compelled, she continued walking toward the light and the light got brighter and brighter until, stepping past a gauzy dividing curtain, she was confronted with a near-blinding fluorescent glare and a tangle of exposed wires.

She stood there, stunned. So, not even light escapes, she thought. Even light becomes a limit, a trope, a convention…

But then a guard barked out, “Oh no! Excuse me! You can’t go in there!”

Obediently, Hero stepped out of the light. Now, of course, the darkness was not as dark as it had seemed. The people did not appear to her as shadows but as distinct individuals: a few college students, an older gay couple consulting the museum brochure, a woman wearing a baby on her back in a sling.

The guard was still moving toward her, her hands outstretched in alarm, but also, no doubt, because—having just re-entered the room—she could barely see.

“I’m very sorry,” the guard said, as she reassumed her post at the limit of the artwork—a limit marked (it had by now become clear) by the thin gauze curtain Hero had unthinkingly stepped through just a moment before. “You’re just really not supposed to go in there.” She seemed more embarrassed than angry, now, though. How, after all, was anyone to know—without the presence of the guard—where the piece ended or began?

Now the bare fluorescent bulb, still glaring at them from the other side of the curtain—the same bulb that had struck her as a sad testament to the demise of art in the twenty-first century, an apocalyptic drive toward the dead centre of things—seemed to Hero, instead, like a revelation. All that input and output! That obscene brightness! That confusion of sockets and wires!

* * *

—

At last, the bride appeared, framed in the doorway. Pretty. A big, open face, wide lips. Something keen—expectant—about her. The dress was all right, too. Pretty classic. Off-white. Lace at the neckline and at the arms, a medium train that dragged audibly on the auditorium’s parquet floor.

The groom’s eyes still wandered, but the bride’s were steady, and she took her time getting down the aisle. The way that she held herself—self-possessed almost to the point of shyness—made it seem as though whatever she was approaching had nothing whatsoever to do with the humiliated groom, the piped-in music, the pressboard altar, the plastic chairs…Instead of wishing for everything to hurry along, Hero found herself willing the bride to check her pace. How slowly, she wondered, was it technically possible to progress down the aisle? Was it possible for the bride to proceed so slowly—so deliberately—that it would take virtually forever for her to actually arrive? Was it possible that, after a certain point, her progress might even begin to reverse itself? That she might begin to be blown, instead, back up the length of the aisle toward the metal doors at the back of the room? Back, still further: out into the hall, the parking lot, and finally back along whatever complicated freeway system she had come?

But, no. Despite Hero’s best efforts, the bride only continued to move steadily forward. At last, she reached the stage and stepped onto it, carefully. The groom offered her his hand; she took it. The celebrant began his address.

“We are gathered today…”

Beside her, Kitty fumbled in her purse.

Hero wondered if the bride and groom had known each other before they started getting married every week.

Finally, from her purse’s depths, Kitty managed to retrieve a Kleenex and now she patted with it at the corner of her eyes and nose.

“Do you, Jason Stanley Ruiz,” the celebrant continued, “take this woman, Alison Nicole Howe…”

If they used their real names…

The tears had begun to flow freely down Kitty’s face. She no longer attempted to wipe them away.

They hadn’t, Hero noted, changed the “love, honour, and obey” part to “love and cherish.”

A quick peck on the lips; perhaps a genuine blush from the groom. Funny how weeks’ worth of practice had not made a public kiss any less clumsy, or embarrassing.

Kitty blew her nose loudly. Then the first notes of “Ode to Joy” sounded and the couple marched together up the aisle.

* * *

—

“Beautiful,” Kitty murmured as they walked together back to Kitty’s room. “Just beautiful.”

But by the time they arrived, the wedding was forgotten. Kitty settled into her favourite chair, and Hero scrolled back through a week’s worth of Channel 10 news broadcasts, then pressed Play. Zoe’s face, open-mouthed—frozen mid-sentence in a sort of Munch-like scream—reassumed its customary proportions. The steady rhythms of her voice suggested a comforting equivalence between the extraordinary and the mundane. Hero crossed the room to the whiteboard and picked up the dry-erase pen attached to the corner of the board by a string.

She couldn’t think what to write.

A university in Texas was in lockdown after an attempted shooting earlier that morning, announced Zoe. El Chapo’s pilot had been caught and arrested somewhere.

Hero snapped the lid off the pen. “Quinn enjoying his first weeks at school!” she wrote. The point was not, after all, originality.

She snapped the lid back on the pen, then sat down next to Kitty to watch the news. An aerial view of the Texas university flashed across the screen. Someone’s voice, crackling through a broken cell phone line, reported “absolute panic.” It was impossible for Hero not to think of Quinn—for a series of unlikely images to run in sequence through her mind. She remembered hearing about this incident briefly, last week, but it had barely registered. She couldn’t remember if anyone had ended up dead.

Zoe’s face once again splashed onto the screen; she held the camera’s gaze steadily. Then, after a slight pause and an audible intake of breath, she announced that a 3.6 magnitude earthquake had shaken the Big Bear region of the San Bernardino Mountains.

Kitty reached over and patted Hero’s hand. “That’s wonderful, dear,” she said. “I’m so glad Quinn’s enjoying his school.”

Now, Hero wished she had written something—anything—else.

Why, she wondered, hadn’t she written something true? “I don’t know how to talk to my son.” “I walked behind James Turrell’s light projection last week and saw the bare bulb, all the tangled-up wires.”

She was tired of lying. And pretty well everything she said these days was a lie. How could it not be when she hadn’t told anyone—certainly not Kitty—that Quinn was living with Rog now? That her only contact with her son amounted to the roughly two hours they spent together each day in the car, sitting in traffic, in near silence, while Quinn’s iPhone played insipid music that actually sounded like it was trying not to be heard…

But it would have been useless to explain this to Kitty. It would only be a matter of time, a few minutes, maybe, before she would be forced to explain it all over again. Half the time these days, Kitty didn’t even remember that Hero and Rog had split up. She’d ask about him as if fifteen years hadn’t gone by. Hero had given up trying to correct her. It just didn’t do anyone any good, she told herself. Going over it all again, always as if for the first time.

“Yeah. It’s a great school,” Hero said. “He’s liking it a lot.”

But these days, even when Hero didn’t correct her, she found herself uncomfortably “transported” talking to Kitty. As though it was not just Kitty who occupied an earlier time in her life when nothing that had already happened in it had already happened that way. Questions that she at other times managed to avoid would surface, suddenly, against her will: What had “happened,” exactly, Hero would wonder. And when? When had Rog, for example, gone from conceiving of the pool business as a sort of Ed Ruscha meets Robert Smithson experiment in form—“popular land art

,” he had called it—to a life calling? He didn’t make “land art” anymore, no. He made “actual money”—something he had found occasion to remind Hero of more than once even just this past month.

Hero had never made “actual money.” But that wasn’t what bothered her; she was nearly certain of that. What bothered her was that she hadn’t made—or done—anything else either…at least not in a long time. When exactly (she would, in Kitty’s presence, begin to wonder) had she begun to spend more time making mental lists as to why it was equally valid to cultivate the “aesthetic and creative development” of three-year-olds as it was to cultivate her own? She was still pretty certain her reasoning was correct. The hubris of an artist, especially after a certain age and without any corresponding public reputation, was always embarrassing. But how could one ever really know (she would wonder) if one’s own reasoning process wasn’t ultimately unreasonable? An irrational desire to make sense of the present despite of, or in accordance with, the past? A way not of perceiving, but instead of forcing the connections, while life itself continued to flash steadily by, in a series of discrete, irreconcilable images…

In any case, it was pointless and unfair to want to go back, Hero instructed herself. It just didn’t make sense. You couldn’t pick and choose like that; you just couldn’t.

* * *

—

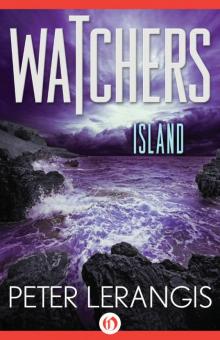

Island

Island Tiger, Tiger

Tiger, Tiger Quartet for the End of Time

Quartet for the End of Time This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories

This Will Be Difficult to Explain and Other Stories The Sentimentalists

The Sentimentalists